Episode 2: The Discovery

- Sara

- Oct 23, 2025

- 4 min read

Skyline Drive, Shenandoah National Park

(photo cred: Matthew Traucht, The Cultural Landscape Foundation)

In late May 1996, Shenandoah National Park was at its most alive. Lush green ridges, dogwoods in bloom, and families pulling off Skyline Drive to capture endless mountain views. The park felt like a sanctuary, a world apart.

But that illusion would shatter when rangers stumbled upon a hidden campsite deep in the backcountry.

A Simple Hike, a Quiet Freedom

End Point of Whiteoak Canyon Trail, Shenandoah National Park

(photo cred: GoHikeVirginia.com)

Julie Williams and Lollie Winans came to Shenandoah seeking what so many hikers chase: freedom. A few days away from expectations, labels, and being seen. They arrived on May 19, 1996, with Julie’s golden retriever, Taj, and a backcountry permit tucked inside a waterproof bag.

Their camera, later recovered by investigators, told a story that words couldn’t. Smiles beside waterfalls. Hikes through Whiteoak Canyon. Two women at peace in the wilderness.

On May 24, they climbed to the summit of Hawksbill Mountain, Shenandoah’s highest point, and took their final photographs.

“Their camera would later reveal a quiet kind of joy — snapshots of two women completely at home in the wilderness.”

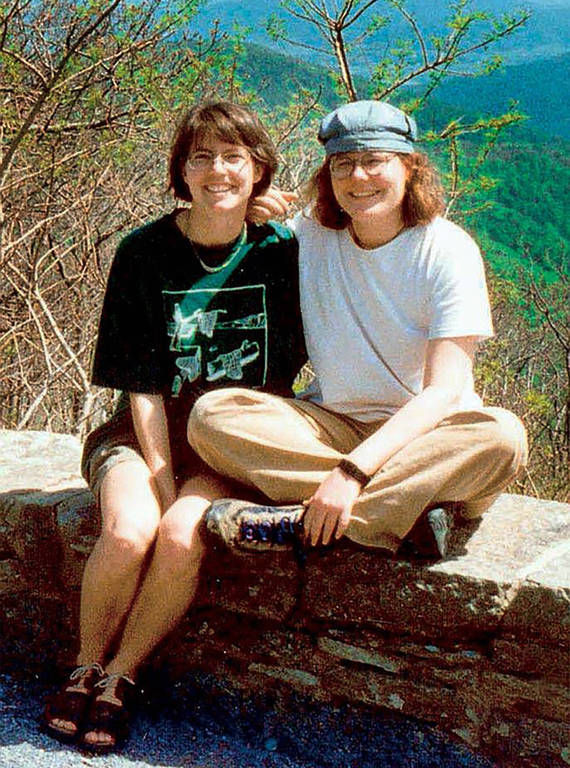

From our best guess of matching up scenery, this is the photo from that area:

Julie and Lollie

That evening, they likely made camp near a quiet mountain stream between Big Meadows and Skyland. It was the last night anyone saw them alive.

The Search Begins

When Julie failed to call home on Memorial Day, her family’s worry grew. By May 31, her father contacted the park. Rangers quickly found the couple’s red Toyota Tercel at Stony Man Overlook and began a series of “hasty searches” through major trails.

Then came the first clue: Taj, found wandering alone but unharmed. By that evening, two rangers tracing Bridle Trail found what they had feared most. A secluded campsite. The tent still standing. The flap half unzipped. Inside were Julie and Lollie, their hands bound, their mouths sealed with duct tape, and each with fatal knife wounds.

“The forest’s silence had been broken forever.”

Fear Spreads

For days, park visitors continued hiking and camping, unaware that a double homicide had turned Shenandoah into a crime scene. When the Park Service finally announced the murders, they called it an “isolated incident.” The FBI used the word “random.”

Outside the park, those words brought no comfort.

1996 coverage from the Richmond Times-Dispatch

The national reaction was swift. Newspapers across the country ran headlines warning that violence had invaded the idyllic world of backpackers. For hikers, the sense of sanctuary was gone. “We don’t hike alone anymore,” one said. Even park staff admitted fear had crept into a place that once felt untouchable.

Here's a news reporter interviewing campers right after this happened:

And another reporter interviewing hikers:

A Community in Mourning

In Minnesota and Michigan, the loss rippled through hometowns and families. Two funerals, two states, same day. Hundreds of mourners struggled to comprehend how two women who loved the outdoors could meet such an end within it.

At Woodswomen, the outdoor organization where Julie and Lollie first met, the grief was especially deep. Their murders struck at the very idea that women could claim space in the wilderness safely.

“Their deaths cut to the heart of what it means to feel free — and what it costs to be seen.”

The Question of Motive

As investigators worked quietly, another conversation began to rise — this one led by the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. In a letter to Attorney General Janet Reno, advocates urged federal authorities to consider whether the murders could have been anti-lesbian hate crimes. Their fears were not unfounded. Eight years earlier, on another stretch of the Appalachian Trail, Rebecca Wight was murdered and her partner, Claudia Brenner, wounded in a hate-motivated attack. Reno’s office responded that all motives were being investigated, including bias, but acknowledged the harsh truth: in 1996, sexual orientation was not federally protected under hate-crime law.

Here is a newscast from June 6, 1996 sharing that a reward has been offered.

The Investigation Stalls

Despite a flood of early tips, leads soon unraveled. No weapon, no witness, no suspect. Only silence. It was as if the forest itself had swallowed the truth.

But a year later, a new name would surface after a Canadian cyclist named Yvonne Malbasha was attacked on Skyline Drive. Her story would draw investigators to a man whose name would dominate the Shenandoah case for years to come.

Reflection

When I first listened to the rangers describe the scene they found, what stayed with me wasn’t only the violence. It was how ordinary everything else was. The sound of the stream. The tent zipped halfway open. The gear was neatly stacked, waiting for a morning that never came.

Julie and Lollie went into those woods looking for peace, and for a few days, they found it. The tragedy is that their story reminds us how fragile that peace can be, especially for those who live and love outside the lines of safety the world still draws.

For many of us, the wilderness has always been where we go to feel free. And yet, freedom without safety is not freedom at all. Thanks for listening.

— Sara Reid, Host of SEQUESTERED

Drop us a line at sequesteredpod@gmail.com!

Credits

SEQUESTERED is created by Sara Reid and Andrea Kleid.

Hosted and produced by Sara Reid.Written and researched by Sara Reid and Andrea Kleid.

Theme music by Night Owl. Original music by Andrew Golden, listen to his full song “Shenandoah” wherever you listen to music.

Comments